Last week we witnessed a critical vulnerability in the WordPress visual builder Bricks: https://snicco.io/vulnerability-disclosure/bricks/unauthenticated-rce-in-bricks-1-9-6.

In this article I will describe how the attack happened, add a bit of theory for those who are not so tech-savvy, add procedures for cleaning up the site and tips for preventing future attacks.

What happened?

Due to the severity of the problem, the Bricks creators quickly prepared a patch and were transparent about the issue – all licensees received several urgent emails and highlighted the need for a patch in their FB group.

From my point of view, that was the best way they could have proceeded. If they had proceeded more quietly, the result would have been many infected sites with sleeping malware that would have unnoticed for a long time.

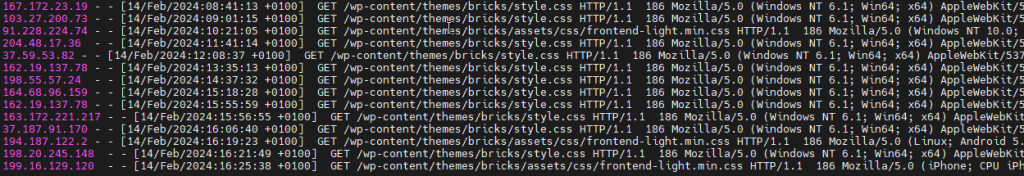

I have to admit that I have probably never seen such a quick response from attackers. Immediately after the first information about the existence of the vulnerability, I started to observe scanning to see if Bricks was installed – this was in preparation for a quick application of the exploit once it could be created. The great advantage of open source is that we can easily examine what changes the patch has made and deduce what we need to prepare for. On the other hand, the attacker is doing the same thing, so it’s a race against time.

You can found some malicious code from that exploit here. I extracted them from my honeypots.

The real attacks originated mainly from the following IP addresses:

- 103.187.5.128

- 149.202.55.79

- 5.252.118.211

- 91.108.240.52

Discussions on FB and other channels showed that this was the first time many users had seen such a serious, actively exploited vulnerability. As soon as we were made aware of the problem, we began patching all customer sites and our own sites that use Bricks Builder. There is of course a risk that the update will break the site, but we have a mantra that “it is better to have a broken site than a compromised one”.

We prepared a bash command that we ran on the servers under our management that updated Bricks via the WP CLI:

find / -maxdepth 8 -type d -path "/themes/bricks" -o -type l -lname "bricks" | xargs -I {} sh -c 'cd "$(dirname {})/.." && echo 'Bricks found in: $PWD' && wp theme update bricks'We ran the command twice, in case WP didn’t know about the update the first time, and to make sure everything was updated successfully. The whole process only took a few minutes, and we survived the attacks without any problems.

From comparing the changes between 1.9.6 and 1.9.6.1, we knew that the attacks would come through the REST API, so we routed the Bricks endpoint requests to a separate log for further analysis to catch real attack attempts and prepare virtual patching rules for them in ModSecurity.

Progress of Attack

However, many users were not so lucky. For them, the next part of this article will discuss what the attack may have caused and what recovery procedures are in place.

The following POST request to a WP REST API was used for the attack:

/wp-json/bricks/v1/render_elementI would like to remind you that there are 2 main types of HTTP requests – GET, which puts all the data sent in the URL (the parameters are after the ?) and POST, where the data is embedded in the communication and is not visible at first glance.

The attack request was sent using the POST method, which means that simple security filters (such as security rules in .htaccess) could not catch it because they only look at the GET request address. It should also be noted that the same request is legally made by Bricks when editing site in the editor. So it is not possible to block just this request or even the whole REST API. A malicious request can be tentatively identified by the fact that it comes from an unknown IP address, does not contain a site referrer, and does not end in an error – you can get these info from access log (ask your host if you don’t access to them).

Remote code execution (RCE) is one of the most serious type of vulnerability. This is because an attacker could do almost anything to the site – they could upload backdoors, create their own users, obtain passwords to the database and other services and APIs, steal license keys, crack user passwords, get personal data (especially if you run eshop or store lead forms), attack other sites on the hosting, and much more. So the impact of an attack is hard to predict and it is better to plan for the worst when remediating.

Remove the infection

So let’s go through the process of getting rid of a possible infection. There are three main scenarios:

- I have a clean backup

- I do not have a clean backup and the site has not been completely destroyed.

- I don’t have a clean backup and the site has been completely destroyed.

In either case, it’s a good idea to first download a full backup of the site – FTP files and database exports from PHPmyAdmin or similar tools. It’s also a good idea to shut down the site to prevent constant reinfection during the recovery process. This can be done, for example, by enabling http authentication (.htpasswd) or use a .htaccess rule to allow your IP address only:

Order Deny,Allow

Deny from all

Allow from my.ip.ad.drRestore from a clean backup

If I have a clean backup from before the infection, the best thing to do:

- Keep calm.

- Delete all site and database files – I want to explicitly point out here that it is not enough to just replace the files from the backup, you really need to delete everything – the malware may have uploaded backdoors to the site to files that are not in the backup, and simply copying the files would leave them there.

- Upload the files and database from a clean backup and upload the updated bricks.

- Change the password to the database – this may require cooperation with the hosting – the attacker may know the original password and so be able to re-enter the site via the hosting’s PHPmyAdmin, for example.

- Reset all users’ passwords – the attacker may have obtained password hashes from the database and, unless the user has used a very strong password, may be able to crack it. This will make it difficult for an attacker if you have strong bcrypt hashing enabled.

- Change the encryption keys in wp-config.php https://api.wordpress.org/secret-key/1.1/salt/ or via wp cli:

wp config shuffle-salts - If you use connections to external services (SMTP, various APIs of other services) you need to change these passwords and API keys as an attacker may now have access to them.

- Make sure that the sites on the hosting are well isolated from each other – this requires more technical skills, but as a first step you can check this using my Mini File Browser and try to see if the you can access outside from the site folder and can run system commands – the infected site could indeed infect other sites on the server. If permissions are not set correctly or system commands are enabled, it is worth checking the server cron (crontab -l, systemctl list-timers, /var/spool/cron/<username>)for malicious commands.

- Malware can also actively run as a process in RAM, unfortunately this is difficult to detect without sufficient privileges on the server. Ask your host for help.

- It’s still a good idea to run a malware security scan, using Wordfence for example.

Restoring a clean site without a backup

If a clean backup is not available, a few extra steps are required. Again, make a recent backup of the site (files and database) – we will now be actively working with this.

- Download the backup and delete all site content.

- Search wp-content/uploads for any hidden PHP files and inspect and delete them – normally there shouldn’t be any, but some plugins may create a folder where some will be present (PHP snippets plugins do this, for example)

- Import a database backup into PHPmyAdmin and make some checks:

- Check the wp_users table (the wp_ prefix may be different) and check for any unknown users

- Check the wp_post table to see if the content column contains any suspicious external links, scripts or iframes (not 100%, but usually enough):

SELECT * FROM wp_posts WHERE REPLACE(post_content, 'http://mydomain.com', '') LIKE '%http://%'.

SELECT * FROM wp_posts WHERE REPLACE(post_content, 'https://mydomain.com', '') LIKE '%https://%':

SELECT * FROM wp_posts WHERE post_content LIKE '<script

SELECT * FROM wp_posts WHERE post_content LIKE '<iframe

the occurrences found need to be revised and the bad code has to be removed - Check the wp_postmeta table for suspicious links, scripts and iframes.

SELECT * FROM wp_postmeta WHERE REPLACE(meta_value, 'http://mydomain.com', '') LIKE '%http://%'.

SELECT * FROM wp_postmeta WHERE REPLACE(meta_value, 'https://mydomain.com', '') LIKE '%https://%'

SELECT * FROM wp_postmeta WHERE meta_value LIKE '<script

SELECT * FROM wp_postmeta WHERE meta_value LIKE '<iframe

- Download a clean version of WordPress from the official repository and restore it.

- Restore the freshly downloaded Bricks and any plugins in use. If you are using the Bricks Child Theme, you will need to check it to see if any malicious code has been added.

- Restore clean wp-content/uploads

- Proceed from step 3 of Restore from a clean backup ^.

Restoring the destroyed site

If the site has been completely destroyed, you should try to recover as many fragments as possible. You can try to check the FTP remnants, very old backups, cached FTP tools files, or still-open site bookmarks. If the site is older, you may be able to find some of the content on archive.org.

Future attack prevention

If the recovery was at least partially successful, it would be a good idea to think about preventing similar problems in the future. Such a destructive vulnerability can occur in almost any component. Personally, I would focus on the following steps:

- Evaluate the functionality of backups or add additional backup solutions (e.g. Updraft Plus).

- Consider deploying a security plugin – I would recommend Wordfence, but if you want something lighter you can try BBQ Firewall.

- Consider using a solution for bulk sites management and updates (MainWP, ManageWP,…) and implement a process for auditing the site.

- Consider using more secure hosting (especially if you have found that site isolation is not sufficient)

- Actively monitor the site for some time to see if anything unusual is happening – again, Wordfence will help with this

- If you have your own server, I’d consider running regular tests with the WP CLI (

wp core verify-checksums, wp plugin verify-checksums –all, use WP CLI Doctor) and possibly deploying a Wordfence CLI for regular checks.

FAQs

WORK IN PROGRESS…

Should throw Bricks away? – No

Should I disable REST API? – No

Should I file a lawsuit against the creator or security researchers – No!

Should I use “Hiding” plugins – No

Should I use security plugin – Yes

Should I use backup plugin – Probably yes

Check my WordCamp Europe talk to more security tips:

Sysops tips

Useful commands:

If you have your own server/VPS and have root permissions the following commands may be useful.

Check all crontabs:

for user in $(cut -f1 -d: /etc/passwd); do echo "Cron jobs for $user:"; crontab -u $user -l; doneCheck running processes for all users:

for user in $(cut -f1 -d: /etc/passwd); do echo "Running processes for $user:"; ps -u $user -o pid,cmd --no-headers 2>/dev/null || echo "No running processes for $user"; echo; doneCheck running processes with open ports for all users:

cut -f1 -d: /etc/passwd | xargs -I {} sh -c 'echo "Running processes with open ports for {}:"; ps -u {} -o pid=,comm= --no-headers 2>/dev/null | xargs -n2 sh -c "lsof -nP -i -a -p \$1 2>/dev/null | grep -q . && echo \$2 \$1 && lsof -nP -i -a -p \$1 | grep -v CLOSE_WAIT | awk '\''{print \$1, \$9}'\''" sh; echo'Run WP CLI command on all WP sites:

find / -type f -name wp-config.php -print0 | xargs -0 -I {} sh -c 'cd "$(dirname {})" && echo "WP config found in: $PWD" && wp core verify-checksums'Find all files where the current user can write/read:

find / -type f -writable 2>/dev/null

find / -type f -readable 2>/dev/null

Find all files in current directory modified in 7 days

find . -type f -mtime -7Useful tools:

- Wordfence CLI

- Aide, Tripwire

- Linys

- Maldet, ClamAV

- RKhunter, Chkrootkit

Leave a reply to WordPress Builders: journey from phpinfo() to RCE – Vladimir Smitka Cancel reply